An Interview with Michael Friedman

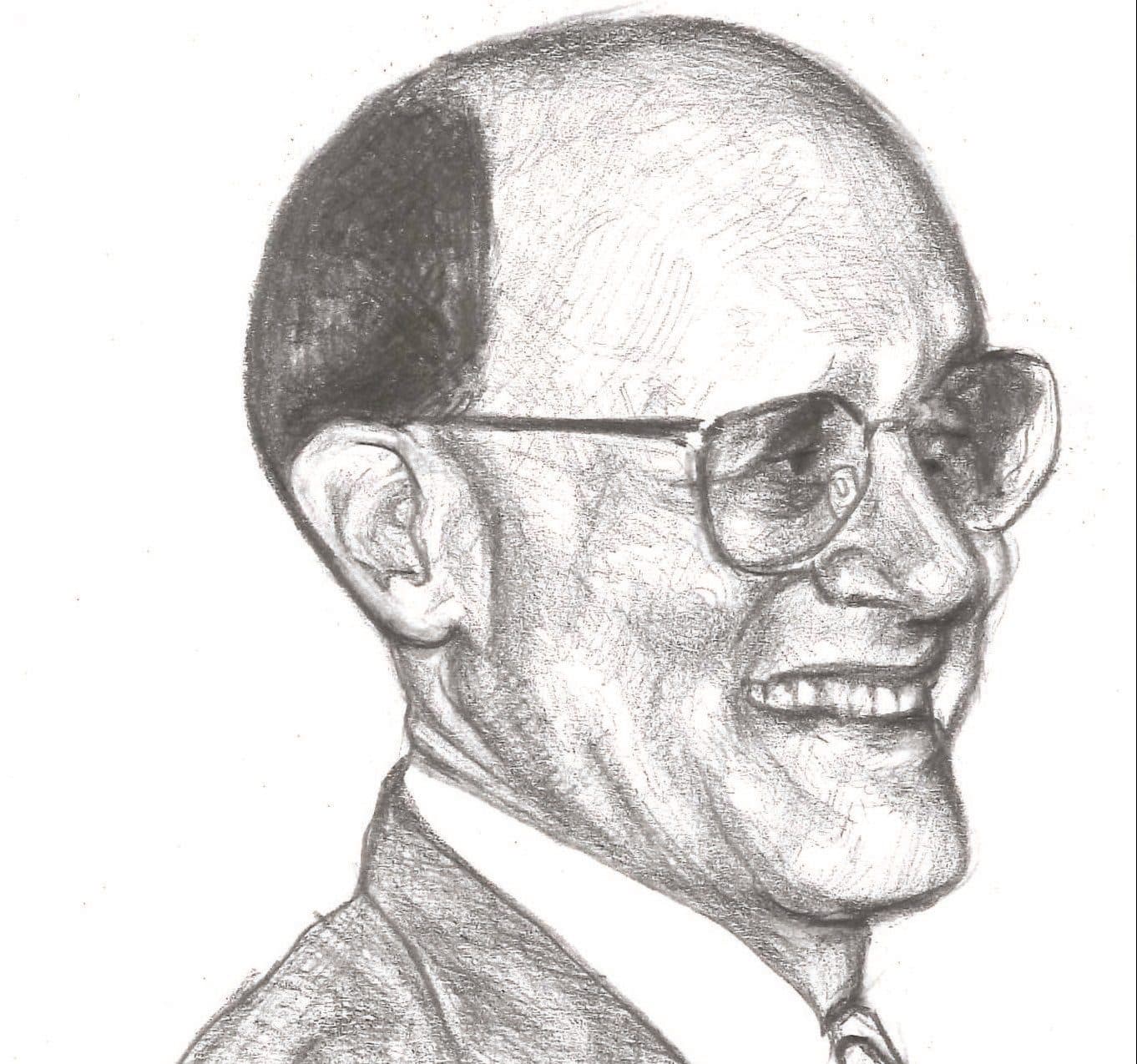

——-Illustrasjon: Jenny Hjertaas Ljønes——–

Den trettende årlige internasjonale Kant-kongressen, organisert av Norsk Kant-selskap, fant sted første helg i august i lokalene til Det juridiske fakultet, på Universitetet i Oslo. Flere hundre akademikere fra Europa, USA, Sør-Amerika, Øst-Asia og Australia møtte opp for å delta på rundborddiskusjoner og foredrag med sine fagfeller som utspilte seg i parallelle sesjoner fra morgen til kveld på engelsk, tysk og fransk. Samtidig som om årets arrangement rettet et spesielt fokus på Kants politiske tenkning og rettsfilosofi, gjenspeilet i undertittelen «The Court of Reason», favnet foredragene over alle aspekter ved Kants tankevirke og dets påvirkning. Alt fra teologi og metafysikk til matematikkfilosofi og til og med Konfutsianisme var berørt. Spesielt frie til å bestemme sitt eget tema var de 14 æresgjestene i sine hovedinnlegg som de fremførte til fullsatte saler. Blant dem var Michael Friedman, vårt intervjuobjekt, som talte om fornuftens autorative rolle i erkjennelsens arkitektur slik den fremstilles i Kritikk av den rene fornuft.

«Første kritikk», som boka også kalles, utgjorde samtidig temaet på vår ukentlige lesergruppe. Det var i forlengelse av diskusjonene vi har hatt der at vi oppsøkte kongressen i håp om å få svar på våre innbyrdes fortolkningsuenigheter om kjernebudskapet i Kants transcendentale idealisme. I over et års tid har vi kjempet i motbakke for å forstå dette verket, som er beryktet for sine enorme terminologiske beholdninger og kryptiske formuleringer der det skjuler seg lag på lag med hardt tilkjempede innsikter om den menneskelige erkjennelses relasjon til virkelighetens egentlige natur (ding an sich—tingen i seg selv). Sammen med en håndfull andre entusiaster inkludert Emeritus Steinar Mathiesen, som står for Kritikkens norske oversettelse, samles vi hver helg til kaffe og pannekaker for å komme til bunns i denne gåtefulle åndslabyrinten. Da Mathiesen sluttet seg til gruppen forrige vinter, håpet vi omsider å kunne få en autorativ uttalelse som ville nøste opp i våre uenigheter. Men der han stirrer intenst inn i første kritikk og finleser de indre kapitlene ett setningsledd av gangen, er han like maktesløs som det vi var — enda det er hans egen oversettelse han sitter med i fanget. Sannheten er at kranglene bare tiltok i vår lille lesesirkel. For hver dag som gikk opplevdes det som vi drev stadig lenger fra hverandre, og ikke minst fra den gamle enigmaen fra Königsberg.

Stridighetene dreide seg om Kants teoretiske filosofi, slik som hans syn på de rene fornuftsdommers universelle gyldighet. Hvordan kan Kant generalisere sine argumenter om sensibilitet og forstand, reseptivitet og spontanitet, sansning og kognisjon, og ikke minst fornuft – det noen kaller hans «diskursivitetstese» - til å gjelde alle mennesker? Skal man forstå skillet mellom erfaringsverden (det fenomenale) og det som eventuelt måtte overskride den (det noumenale) som et metafysisk eller epistemologisk skille? Og gjør Kant seg skyldig i en uheldig form for «psykologisme», som tar utgangspunkt i menneskelig psykologi, i stedet for objektive forhold som er felles for alle erkjennende vesener som sådan? Vi oppsøkte så ulike fortolkere som Henry Allison, Ernst Cassirer og Martin Heidegger, men alle galopperte i hver sin retning og virvlet opp skyer av terminologisk krittstøv. At ekspertene tolket Kants transcendentale idealisme på så forskjellige, og ofte gjensidig utelukkende, måter, gjorde at vi var i ferd med å miste håpet. Men kanskje kunne en nøktern amerikaner skolert i den analytiske (anglo-amerikanske) filosofiske tradisjonen, tjene som en upartisk dommer, en «Court of reason»? Kunne Michael Friedman komme til unnsetning? Michael Friedman fant veien til Kant fra sine studier av vitenskapshistorie og matematikkfilosofi. Denne syntesen har resultert i bøkene Kant and the Exact Sciences (1992) og Kant’s Construction of Nature fra (2013), i tillegg til en rekke tidsskriftpublikasjoner. Friedman har markert seg som en Kant-fortolker som vektlegger den vitenskapelige og matematiske kanon i utformingen av de transcendentale argumentene, til forskjell fra en mer «pur» filosofisk og anti-skeptisk lesning av argumentene. I følge Friedmans lesning, dreier Kants teoretiske filosofi seg ikke i første rekke om å tilbakevise skeptisisme om den ytre verden, men snarere om å finne de etablerte vitenskapenes grunnantagelser. Anti-skeptiske fortolkninger, som Strawsons Bounds of Sense (1966), konsentrerer seg om hvordan Kant kan vise at syntetisk apriori kunnskap – som også betyr: sikker og objektiv kunnskap – er mulig. Det er derimot et annet spørsmål som opptar Friedmans Kant: Syntetisk apriori kunnskap er mulig, men hvordan?

Friedman mottok doktorgraden i 1973 ved Princeton, og har vært professor ved en rekke universiteter. Nå er han Suppes Professor of Philosophy of Science ved Stanford. I tillegg til sine bidrag til Kant-forskningen, har han mange publikasjoner om filosofihistorie, særlig innen den tyske filosofien etter Kant, og derunder om den logiske positivismen. I boka A parting of the ways: Carnap, Cassirer and Heidegger (2000) tematiserer han skillet mellom en humanistisk orientert kontinentalfilosofi og en vitenskapelig orientert analytisk filosofi i det 20. århundret, og viser hvordan skillet kan forstås som et resultat av de tre filosofenes ulike lesninger av Kant.

Fortapt i menneskemylderet på den enorme kongressen, klarte vi ikke å finne frem til Michael til avtalt tidspunkt. Da vi endelig fikk fatt i ham var han kraftig irritert over at vi kastet bort lunsjpausen hans, noe som gjorde at minst én av oss ble veldig stresset, men vi var enige om at ingen ting skulle komme imellom oss og Kant. Denne cerebrale østkystamerikaneren, som tatt ut av en film av Woody Allen, gjorde at vi følte oss som to klossete skogsmenn i sammenlikning. Vi slo oss ned i den sommertrette Aulakjelleren i Domus Media. I det samme vi steg ned fra den iskalde minglepraten og inn i filosofiens verden, forduftet alle disse spenningene. Vi snakket om Newtons bevegelseslover, om den tyske romantikken, om Carnaps relativiserte apriori, og Leibniz’ substansbegrep. På et tidlig tidspunkt ble det imidlertid klart at Friedmans Kant ikke var den Kant vi ønsket oss: Den dypsystematiske og hyperteoretiske på jakt etter at filosofenes hellige gral: Å legge grunnlaget for all kunnskap og legitimere metafysikken en gang for alle. Friedman vektlegger begrensningene som Kant setter for metafysikken, han mener at Kants system står og faller på gyldigheten av Newtons bevegelseslover, og han forfekter en instrumentalistisk eksistensberettigelse for Kants filosofiske system: Når det kommer til stykket består Kants store bidrag i at han la et grunnlag for rasjonell samforståelse mellom mennesker. Og hvis du kommer fra et mer teoretisk-filosofisk hold og ikke synes dette høres tilstrekkelig ambisiøst ut, vil Michael Friedman svare at det tross alt er «pretty good».

Describe your path from analytical philosophy to Kant scholarship?

I never had a Kantian as a professor, although I learned a lot from the great Kantian people like Charles Parsons. I always liked Kant, even as an undergraduate. But I never had any training in Kant until I started thinking that I could engage with Kant’s philosophy of science in a new and more thoroughgoing way. From reading and interacting with inspriring scholars at my university, I learned how to do just that. Even before I was introduced to analytic philosophy, Kant was the object of my highest admiration. When I read Bounds of Sense by Strawson it struck me as the best thing that I had ever read. I thought that if that is Kant, then Kant is great. Then I began reading The Critique of Pure Reason, which was not so easy to understand as Strawson, but I thought it was an amazing project. But there was a problem: The first thing they taught you in the philosophy of physics was that Kant was too devoted to Newton. He even makes a mistake by saying conservation of substance means conservation of quantity of matter. He is bringing in Newton’s physics, which is illegitimate; that is not philosophy. So the position is: We have to save Kant, but in light of 20th century developments in theoretical physics we cannot save his philosophy of science; because we cannot save Newton. But maybe we can save the categories, and maybe we can save his analysis of experience.

In other words, your interest in theoretical physics brought you back to these historical issues?

By reading Gerd Buchdahl’s book, Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Science, I saw how a historical approach can reveal Kant’s unbelievable insight into Newton. At least some will agree that Kant interpretation of Newton’s conception of absolute space in the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science was a great philosophical achievement. So I asked myself: How do I combine the philosophy of physics and my knowledge of modern logic with Kant? I thought I could do this through a historical approach, and that is how I got where I am.

Do you discern any specific trends that give you faith that today's Kant scholarship is headed in the right direction?

Naturally, I follow discussions on Kant’s philosophy of science, although many philosophers of science disagree with me, and vice versa. In my view, the emphasis on morality and the practical role of the noumena is a promising field of research. In recent years, the awareness of this role has increased, through the discussion of the fact of reason that was introduced by Dieter Heinrich in the German tradition. Rawl too wrote articles about the fact of reason, which inspired a lot of moral philosophers. Meanwhile, many scholars forget about the Kant’s practical philosophy; they just want to do the theoretical stuff.

This conference brings together a cumulation of philosophers that all self-identify as “Kantians”. But what does that mean? Apart from appreciating the same primary literature, is there any particular belief or theoretical commitment that you all share, or anything else that you all have in common? Or are you each other’s peers only in name?

There is a famous joke: If there are two Kantians in the room, there are at least three mutually incompatible interpretations. There is a lot to that joke. Kant interpretation is notoriously difficult, and interpretations differ greatly. There are scientific, phenomenological, even phenomenalist interpretations of the old fashioned Berkeleyan kind. There are quasi-naturalistic interpretations, hermeneutic, and so on. The only thing that unites us all is that we take Kant very seriously. Personally, I take Kant to be the single most important modern philosopher. All philosophers after Kant seems to be reacting to him, whether they reject his ideas, accept them, or try to improve on them.

How would you define transcendental idealism? Does Kant provide a direct argument for this position, or is it the outcome of a larger cost-benefit that can be extracted from the Critique in its entirety only?

Kant has several direct arguments in the Critique. As you know, the Transcendental Aesthetic contains an argument about apriori knowledge of geometry. Later on, in the Transcendental Dialectic, he introduces the antinomies: This is a famous argument from transcendental idealism, to the conclusion that certain questions about the world -- such as whether it is finite or infinite as a whole -- that cannot be answered in the positive either way. There is no way to know. The Transcendental Analytic contains the Transcendental Deduction. It concludes that the categories have objective reality, but only when applied to spatio-temporal forms of intuition; that is the schematism. Those three arguments make out the case for his transcendental idealism. The Aesthetic, Analytic and the Dialectic each contain a fairly straightforward main argument. Now, some do not like the way Kant proceeds. For instance, the post-Kantians hated his dualism, the separation of the faculties of sensibility and understanding. He should have had a single principle as his point of departure, or so they thought. They were afraid that a system based on several principles would render impossible a rational understanding of their mutual relation. Earlier, you expressed some similar concerns: “If it is just the human sensibility, what good is that? It should be for all knowers.” But from my point of view as a philosopher of science, I think Kant departs from the most reliable knowledge of nature in his time, most importantly, Newton and geometry.

So, you are saying that the post-Kantians objected to this multiplicity of principles. By his bridging of understanding and reason in the third critique, did Kant anticipate this criticism?

He did the best he could. In the third critique he still had nature and freedom, he had understanding and he had reason. Also he had what he took to be a bridge between them, and it was a pretty good one. And the post-Kantian idealists and the romantics liked the third critique because of that.

Would you even try to explain transcendental idealism to your mother?

I do speak to my mother about my work. She is now 93 years old, and got a philosophy degree very late in life. She is very interested in existentialism and all kinds of spiritual things. Every weekend I tell her what I am doing, and she gets some idea out of it. She is very insightful, although not into the scientific details.

We think there are two types of Kantians: The ones who see Kant's synthetic apriori as a constraint on metaphysics, and those who see it as a liberation. To which type do you belong?

In general, I take Kant to be more anti-metaphysical. In my view, the synthetic apriori is an epistemological notion. Kant argues that science has to presuppose certaintruths, such as the laws of motion. The neo-Kantians wanted to continue along those lines: Let us investigate the current science and its necessary presuppositions. You may call this a “fact of science”-approach; the philosopher just takes science to be the best model of nature that exists at a certain time. The question for the philosopher of science goes like this: What presuppositions make scientific knowledge possible? The presuppositions, then, have no authority independently of science.

You've been interpreted as placing the Newtonian laws of motion, on the same level as other synthetic apriori truths. Do you think that, according to Kant, the two are equally basic in our knowledge of nature?

The laws of motion are not quite on the same level as certain facts of experience that follow from the universal validity of the categories, such as “every event has a cause”. One could say that the laws of motion are synthetic apriori, but not in the purest sense, because they contain empirical concepts.. Then again, other interpreters could respond: While the concepts of motion have empirical content, the concepts may or may not be instantiated by events in time and space. Therefore, the laws of motion have universal validity too. But that reasoning does not suffice, because Kant is concerned with absolute and relative space. For the motion to be perceptible, the observer needs more than empty space. According to Newton, one cannot determine movement of an object relative to absolute space.

Just central of a position do the synthetic, Newtonian truths occupy in Kant's system?

They are at the core. The basic laws of motion or mechanichs, Netwton’s laws, are fixed within Kant’s system. I wrote this big fat book called Kant's Construction of Nature, which is about The Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. My book is 600 pages, while The Foundations is 98 pages. I spent my whole career on the tenet that Newton's mechanics is at the core of Kant's system; you cannot get me away from that.

Instead, what do you think of letting science go its own way and subsequently decide whether Kant is compatible with what comes along?

He is not. He is commited to Newton. Consider, as an example, the differing concepts of substance. Kant derives the concept from Leibniz and the tradition, but alters it by connecting it to Newton’s concept of matter. One cannot simply accommodate all of modern science within Kant’s system. I would need my students to work out the details: An empirical concept offers some wiggle room, so to speak, unlike the categories. The categories result from logic and the schematization of space and time, as shown in the transcendental deduction. All that simple stuff.

If we follow Kant in that the categories are fixed, can't we just replace the Newtonian laws with some Einstein and hold on to the sameessential conception of the structure of reason? How disprutive would such a minor fix be for Kant’s genereal project?

That is a good question. Kant speaks of matter and its instantiations in the category of substance, whereby the category of substance is the quantity of matter. Substance is conserved. In the second edition of the Critique, Kant expanded the first analogy to concern the quantativeness of substance. He did not say that substance is conserved until he wrote The Metaphysical Foundations of Science in 1786.

You have written extensively about Rudolf Carnap. There is a similarity between your interpretation of Kant’s conception of a priori judgements and Carnap’s view that it is up for us to stipulate what is a priori true in deciding which linguistic framework to use in organising empirical data into scientific theories. Do you hold an interpretation of Kant whereby the a priori is similarily up to our chosing?

Yes. The linguistic framework in Carnap has its rules, and those are analogous to the relativized apriori. I like Reichenbach's notion of the relativized apriori. The relativized apriori is what is constitutive of the object of science, within a particular theory. Usually one has in mind theories of mathematical physics, because they seem to have the most precision, the greatest ability to bring into bear the relationship between measurements and the mathematical structures and so forth.

So you think that the most sensible notion of a priori knowledge is for the judgement in question to an indisposable for formulating certain scientific facts. Is this all there is to a priori knowledge?

I'm very sympathetic to the “fact of science”-reading of the transcendental arguments, which goes to say that I reject metaphysical readings of Kant. Of course, Kant calls his own project metaphysical. H.J. Patton calls Kant’s metaphysics a metaphysics of experience, which I think is a good phrase.

In Kant’s analysis of experience, synthetic a priori judgements play the crucial role of placing scientific knowledge on secure ground. However, for the positivists, all a priori judgements are analytic. Please explain.

Das war das Problem. Since Carnap thought that only empirical science has content, all apriori presuppositions had to be analytic. To him, the mathematical and logical frameworks are empty forms. Yet these forms allow theories to bridge mathematics and measurements, which is crucial. The whole point of only accepting analytic judgements as apriori presuppositions is to say that mathematics has no empirical content. Yet you're using the mathematics to represent the empirical structure which ultimately depends on measurements made in the real world. As a result I think that Carnap, by emphasizing the analyticity, strains the connection between empirical science and its presuppositions. I take one of Kant's great insights to be that mathematics is the form of our perception. While the form is not merely derived from logic, i.e. analytic, it cannot longer be taken as synthetic apriori in Kant's sense, i.e. unrevisable. Kant took geometry to be synthetic apriori, which complicates the relationship between mathematics and perception, since we're not stuck with Euclidean geometry anymore.We have at least the three classical geometries. Does that give us latitude for altering the form of perception? The same goes for physics: In Kant's time, the only geometry applied in science, by Newton, was Euclidean. Kant can be generalized from the science of his day, since science kept moving. But everything -- every presupposition, for instance the laws of motion or Euclidean geometry -- cannot be up for grabs all at once. That is, inventions within math and physics does not warrant a Quinean holism, which is an inadequate view of what is going on in science.

Do you agree with Kant that mathematical truths are synthetic? How about geometry?

I tend to agree that most mathematical theories are synthetic; such as any theory that contains a notion of infinity -- you can distinguish between potential infinity, like the number series, and actual infinity, like set theory. These assumptions about infinity I do not think reasonably can be called analytic. On the other hand, first-order logic -- with identity -- could be called analytic. As soon as you posit an infinity of objects, the judgement is synthetic. If geometry takes space to be continuous, or even dense, it has strong infinity assumptions. Some people are interested in discrete geometry, but that does not seem to have any useful application in science.

Does Kant’s theory rely on empirical premises from the very start, even though the theory is instituted to legitimize those very judgements?

I think both Kant and Carnap reject a priorphilosophical level as the foundation of science. The best knowledge of nature resides in the most developed theories of physics. Kant basically said: You cannot reasonably doubt what geometry says, or Newton's laws. We have nothing better than these theories; we understand them. Meanwhile, we do not understand metaphysics; what substance is; what causality is. We only get a handle on the categories through their application to the world we live in. I think Kant argues inductively, rather than deducing everything from the Grunddisziplin, metaphysics. Basically, he says: Math and physics are great. Nobody is arguing about that. He thought that asking for how math and physics are possible would place metaphysics on the firm path to becoming a science .

It seems like you don’t pick out a first philosophy in Kant. Instead you stress the interdependence of his epistemology and the sciences of his time, the Newtonian premises. Are pyramids out of fashion? Like his Enlightenment predecessors, one could think of Kant like a foundationalist, who was trying to find a firm foundation for all our knowledge. Your Kant sounds like he is holding to a more contemporary conception of epistemic justification whereby all our beliefs are up for grabs.

Kant is not a pure coherentist, since certain judgements and certain structures of experience are fixed within his system. Mathematics, space and time as the forms of our intuirion and the basic laws of physics are fixed. Other beliefs can change, but they are always constrained by these certain apriori foundational constraints on knowledge. He hopes that those constraints suffice to explain the rationality of even the more contingent parts of our knowledge. While those more contingent parts would be falsifiable, they are rationally established in this sense: Given the apriori framework that we started with, and given the route we took from that framework to the entirety of our beliefs, our beliefs are rational. It is not a coherentist fact. You could call it a quasi-foundational fact, if you prefer that term. Kant is no naturalist either. In his view, a science of nature must be developed on top of the fundamental laws of Newtonian mechanics. If anything, he is too foundationalist, from our current point of view, about Newton's mechanichs. But if foundationalism attempts more than establishing a rational agreement between humans, that would be overkill from a Kantian point of view. To establish any agreement between humans is a hard enough project. If you could make it apriori and rational, in addition, that would be pretty good.

Seeing as you emphasize this interdependence between Kant’s epistemology and facts of scientific knowledge, you must surely disagree with attempts such as Strawson’s to refute scepticism about the objective or outer world via transcendental arguments inspired by Kant?

I take Kant to be less coherentist than Strawson. Strawson says that there are certain principles without which we cannot even have sensible language. Those principles are analogous to Kant's constraints on knowledge, although Strawson does not fix those principles as firmly as Kant does. Strawson speaks of sensible and non-sensible worlds. Scepticism is refuted, because a skeptical world is non-sensible. This sounds a bit dogmatic to me. I think Strawson ought to provide a deeper explanation of how he gets certain constraints on sense, as Kant did. Kant accounted for the apriori constraints on anything that is sensible to us. He accounts for the exact mathematical forms of sense, and for the inferences about nature. Strawson argues that his bounds of sense refute the skeptic. But the skeptic can still ask: How do you know that those are the bounds of sense?

Later philosophers, like Frege and Husserl, accused Kant of “psychologism”, that is, of limiting his domain of inquiry to mere human cognition. human cognition as his domain of inquiry. Should not Kant’s transcendental or critical philosophy concern truth, knowledge and cognition as such? Not only human psychology, but knowledge for all thinking beings or minds.

No. Our knowledge is based, in the first instance, on the structure of sensibility, on space and time as our forms of intuition. We do not know what form of intuition, if any, other beings might have. Presumably, God is an infinite cognizer, unlike us. But we cannot reasonably assume that all possible finite cognizers share our cognitive structure; in the case of many animals, that is definitely not the case. According to Kant, our spatio-temporal intuition is subjective in the following way: They give rise to universally objective judgements among all human cognizers. The categories might be universal, at least for finite cognizers. But for Kant, the categories are not sufficient for cognition. The categories have to be schematized in space and time.

However, the universality of such theses as “every event has a cause” and “every thing has a property” emanates from the a priori validity of our forms of intuition, time and space. If our forms of intuition could have been different, would that not alter what comes out as true about the world?

We cannot form any determinate idea of what such a form of intuition would be like. On the other hand, we can have a thoroughgoing understanding of our categories. As I said, they might be extendable to all thinking, to all finite beings. According to Kant's analysis, our cognition consists of both the apriori forms of intuition and the apriori categories. Maybe some other animals, or finite beings, have the same forms of intuition as us -- dolphins, or something. That is an empirical question.

So Kant’s entire project must limit its scope to establishing facts that depend on the human mind? That sounds highly contingent.

Transcendental psychology differs from empirical psychology. For Kant, the forms of intuition and the categories resemble logic, that is, certain formal apriori rules that define, as it were, truth. You mentioned Frege in relation to the charge psychologism, and indeed Frege does not limit the laws of logic to human reasoners. That is a difference between Kant and Frege. I have to say, as a footnote, that Frege thought that Kant was right about geometry. Frege thought that the spatial form of intuition transcended his laws of logic.

Do you agree with us that “the human standpoint” is a significant limit on Kant’s ambition? Not only would that mean it is limited to the phenomenal world, but, according to you, also to the human phenomenal world.

Kant's project concerns any being with a spatio-temporal intuition. As I said, we do not know whether we are the only such beings. And in a certain way, does it really matter? We are the ones who have to figure things out; we have to talk to our colleagues. We are not going to other planets yet. If we could agree with everybody on Earth about what we should be pursuing, or even what is true, that would be a tremendous progress. Now we are in a place where there are no truths and no facts, so Kant’s project is not unambitious.

Vi takker Michael Friedman for en frisluppen diskusjon om vår alles kjære Immanuel Kant.